- Home

- Joel Rosenberg

Not Really the Prisoner of Zenda Page 5

Not Really the Prisoner of Zenda Read online

Page 5

No, he was used to danger, even though he would never have said that out loud, particularly in front of Leria, for fear of sounding boastful.

*Well, yes, it would sound boastful — but I would say that it’s true enough, although not so unusual that you should sprain your arm patting yourself on the back over it. Many of your kind have courage. It’s a lot more common than, say, wisdom. As for me, I think wisdom is better.*

But what he wasn’t used to was pretending to be something that he was not, and the dragon — and only a few others — knew just what a fraud he was.

*Get used to it. Dragons aren’t much good at forgetting, either.*

He would have to get used to it, just as he had to get used to looking at fingers that were a trifle shorter and slimmer than they ought to be, or at arms and legs and a chest that were almost devoid of the scars that they should have had, at a face in the mirror that frowned when he frowned, smiled when he smiled, winced when he cut himself, but he could not make himself believe was his.

*You had better start.*

That was easier for Ellegon to say than it was for Kethol to do. The elven wizards in Therranj had changed him, yes, with magic far beyond what any human wizards could do, with spells that didn’t merely create a seeming, the way that Erenor could, but which had altered his flesh irrevocably.

He looked just like Forinel.

Physically, he was Forinel, from the the widow’s peak that stubbornly defied his receding hairline, to the thick black mat of hair that covered his chest and arms, down to the missing toenail on the little toe of his left foot.

He looked like Forinel, but that was only on the outside.

And it was a lie.

Behind him, Leria leaned forward to place her mouth next to his ear. He didn’t resent that she had taken naturally to riding on Ellegon’s back, and in fact was relieved — there was nothing he could have done to protect her from the nausea that racked his guts.

“There’s the Nifet River,” she said, pointing, “and the Ulter Hills begin just beyond, right at the horizon. We fly quickly across farmland and over Dereneyl, and we’ll be at the Residence before noon.”*Or perhaps not. I think it would be a good idea to drop you off in Dereneyl, since we’re not expected. Pirojil and Erenor agree.*

Nobody had asked him, and that was understandable.

Kethol’s jaw clenched so hard that it hurt. He’d been an idiot to agree to take this imposture on.

But it was either that, or let the son and heir of the bitch that murdered Durine become Baron Keranahan. Elanee was dead, but even dead, she would have won. Forinel couldn’t return to the Empire to claim the barony, not with the elven woman that he had married in Therranj, and particularly not with their half-breed child.

Parliament and the Emperor had been about to award Barony Keranahan to Miron, Forinel’s half-brother — Elanee’s son — and if there had been nobody to take Forinel’s place, that is just what would have happened.

That was unacceptable.

Kethol didn’t mind the thought of dying, but losing?

No.

He had to keep telling himself that, that that was the reason why he had agreed, and that it had nothing to do with the way Leria looked at him, the way that her hands and eyes had rested on his hands and eyes. It had nothing to do with the definite certainty that if he did not agree, Leria would find herself in another man’s bed.

It couldn’t be that, after all. She was too good, too fine for the likes of him, and she belonged in a better man’s bed, in a higherborn man’s bed.

No. He had to make it just another way to fight.

He knew fighting, and he was good at it.

*And what do you say to the notion of Dereneyl as the destination, Baron? It’s your call.*

There was no trace at all of sarcasm in Ellegon’s mental voice.

But no, it wasn’t his choice. He was just an imposter. The others were in charge, not him.

So let it be Dereneyl, he thought.

*I’m so glad you agree,*the dragon said,*because I was going to drop you off in Dereneyl anyway.*

***

Spiraling down out of the sky so fast that it made Kethol dizzy, the dragon came to a steep, bumpy landing within the inner walls of the keep.

It must have rained much more heavily here last night than it had in Biemestren — the wind from the dragon’s buffeting wings sent a spray of water from the ground into the air, soaking Kethol thoroughly.

He’d live; he had been wet before.

*Everybody off, and quickly.*

It was risky for Ellegon to drop them off there at all — the Empire in general and Ellegon in particular had enemies, and there was always the chance that some fool with a dragonbane-tipped arrow or spear would be lurking about. A fool, yes — Pandathaway could offer a hundred times the killer’s weight in gold, but collecting it would be another matter, after all.

Kethol quickly unstrapped himself and made his way down the dragon’s broad sides, fingers and toes digging into the rough surface of the thick scales for purchase. When he reached the ground, his knees trembled and threatened to buckle beneath him, but he tensed up, and forced them to lock in place.

He quickly handed Leria down, releasing her as soon as he decently could. It wasn’t right, after all, that somebody like him should be touching someone like her.

She still took his breath away.

It wasn’t just the regular features, the pert little nose and full red lips, the golden hair, bound up for travel, leaving her long neck bare. It wasn’t even the way that she had felt in his arms, her tongue warm in his mouth.

No. It was the way that she had always treated him and Pirojil and Durine like they were real people, and not just blood-spattered instruments. More: it was preposterous, silly little things, like how she couldn’t keep her hands from tending a campfire at night, or how, when she awoke in the morning to find him asleep — or so she thought — across her doorway, she would shake her head and smile.

(Erenor often said, in muttered conversation with Pirojil that Kethol pretended not to hear, that it had been a foregone conclusion that Kethol would fall in love with the first woman who smiled at him, but that wasn’t true. Kethol had been in service to the Cullinane family for years, and had guarded both the late Emperor’s adopted daughter and his wife, and all of them had smiled at him, often, and while he certainly had liked them all, not one of them haunted his dreams by night.

(Then again, what Erenor said and what was true only coincided by accident.)

Pirojil was down almost as quickly as Kethol was, and was at his side, with Erenor not far behind. The two of them made an unlikely pair — Pirojil, large, misshapen, and ugly; Erenor almost a caricature of a wizard, with a lined, bearded face partially concealed in the hood of his gray robes.

Appearances were sometimes deceiving.

Kethol hoped that appearances were sometimes deceiving, although he couldn’t for the life of him understand why somebody didn’t take a quick look at him and start shouting, “Imposter!”

There was a commotion along the ramparts, but the soldiers over by the main gate and the stableboys and house girls in their noontime game of touched-you-last quickly disappeared from sight, the soldiers quietly ducking into the guard shack, some of the children running for the darkness of the stable, others disappearing behind the bulk of the keep itself.

Erenor shook his head and laughed. He had an easy laugh, a laugh that sounded sincere, a laugh that probably was sincere every now and then, if only by accident. Kethol had just had to get used to that about Erenor, although he didn’t have to like it, and he didn’t.

“Standing orders,” Erenor said, “are often obeyed when they consist of making yourself quickly absent when a flame-breathing dragon plops down out of the sky.”

“Shut up,” Pirojil said. “Just get the bags unhooked,” he added, although it was hardly necessary — Erenor’s nimble fingers were already working on the straps.

*It wouldn’t bother me at all if you were to do that a little more quickly,*Ellegon said.*Or maybe a lot more quickly.*

While there was a good chance that the keep was secure, it was vanishingly unlikely that there was nobody in the town below greedy and reckless enough to try to earn the standing Pandathaway Slavers Guild reward for bringing Ellegon down. Dragons were rare in the Eren regions in general, and unknown — well, almost unknown — in the Middle Lands in particular.

Even now, it was entirely possible that nervous fingers were, somewhere, unwrapping a hidden arrow or crossbow bolt, and dipping its tip in a forbidden pot of dragonbane extract before nervously fitting it to a taut string.

“You’re worried about being shot at, I take it?” Erenor asked.

*No.*The dragon’s head curled on its long neck to eye the wizard, its dinner-plate – sized eyes yellow and unblinking.*I just love getting poisoned, don’t you?*

“I’d say sarcasm ill becomes you, Ellegon, but actually, I must admit that I rather like it.” Erenor stepped back. “And, in this, as in so much else, I think I may be of some help. Are you ready to go?”

*I was ready to go before I came.*

“Then …”

The dragon straightened, and Kethol put his hand on Leria’s arm, urging her back and away, trying not to blush when she smiled, and nodded, and folded her warm, soft hand over his callused one.

Erenor’s eyes seem to lose focus, and his smiling face became distant and almost expressionless. His thin, parched lips parted slightly, and harsh, guttural syllables began to issue forth.

This wasn’t the first time, or the forty-first time, that Kethol had heard a wizard pronouncing a spell. Despite knowing better, he tried to remember the syllables, to put them together into words — if you could remember the words, you could speak the words, and if you could speak the words, you could pronounce the spell, and if you could pronounce the spell, you could work the magic — but the wizard’s words vanished on the surface of his mind, skittering about like drops of water on a hot frying pan before they evaporated … gone, forgotten, not merely unremembered but unrememberable.

The spell ended with a sharp, one-syllable exclamation.

The sunlight, flashing on pools of water left from the overnight rain, suddenly became brighter, brighter than the sun itself, a white light that dazzled not only the eyes but the mind.

The wind from the dragon’s wings beat hard against Kethol, and it was all he could do to keep from being thrown from his feet. His eyes dazzled, he more felt than saw the dragon take to the air.

*Thank you, Erenor,*the dragon said, its mental voice already starting to grow more distant.

“My pleasure,” Erenor said. “And, of course, it’s not merely my pleasure — it would be terribly uncomfortable, at least for a very short moment, to have several tons of dead dragon falling out of the sky and landing on my all-too-fragile flesh.”

*Yes, it would, at that.*

Then, in an eyeblink, the blinding light was gone, and Kethol looked back to see the dragon circling above, gaining altitude as he did, huge leathery wings flapping madly until Ellegon stretched his wings and banked, flying off to the west.

*Good luck,*Ellegon said, his mental voice taking on the muted, formal tone that told Kethol that it was intended for all ears — minds — around, and not only his.

*Welcome home, Forinel, Baron Keranahan — it has been a pleasure serving you. And as Karl Cullinane used to say, ‘the next time you fly, please be sure to consider flying on Ellegon Airlines.’*

Whatever that meant. Kethol — and Durine and Pirojil — had been the only ones of the Old Emperor’s bodyguards to survive Karl Cullinane’s Last Ride, but he had never quite understood half of what the Old Emperor said.

Wings stretched out, the dragon flew low over a far ridge, and then it was gone.

Kethol found that he still had his hand folded over Leria’s, so he let his hands drop down by his sides.

***

Erenor chuckled, leaning his head close to Pirojil. “Not a bad entrance, eh?”

Erenor was far too easily amused, Pirojil decided, with the usual irritation.

Faces were already starting to peek out of windows and doorways, and one immensely fat woman — a cook, by the look of the grease-spattered apron — even went so far as to carry a bucket of something out, to dump it on the slop pile next to the stables before, after a quick glare at the newcomers, scurrying back in.

Whatever it was, Pirojil thought, must have smelled awfully horrid for her to be so willing to venture out. The idea of eating here wasn’t at all appealing, if even the cooks couldn’t stand the smell.

Pirojil wasn’t surprised that none of the soldiers had chosen to come out of the barracks at the far end of the courtyard, or from any of the guard posts at the corner towers. A new arrival was always of some interest in an outlying outpost — and to Imperial troops, an outpost didn’t get much more outlying than Barony Keranahan — but arrival by dragonback suggested that the new arrivals were of some great importance, and it never took even a new soldier long to learn that it was wisest to at least try to be in another place when something important was going on.

Pirojil wished he was in another place.

The front door of the keep stood open, cool, dark, and inviting. Normally, there should have been a pair of soldiers on guard, and Pirojil had been wondering whether they would be standing in the black leather corselets that would have them sweating like hogs in the hot sun. Pirojil had stood his share of watches in that leather armor, which never seemed to lose the reek of the boiling vinegar that had turned the leather stone-hard and solid black.

Not that you minded the smell when it caught the edge of an enemy’s blade.

He had silently bet with himself that the watchmen wouldn’t be in armor, that they would just be dressed in linen tunics and breeches, and he hadn’t decided whether that would mean that the discipline among the occupation troops was slack, or that Treseen was smart enough to insist that his men not suffer to no particular end.

It did mean, of course, that they weren’t of the elite Emperor’s Own, because then they would have been wearing their shiny steel breastplates — or, at least, having them nearby, where lesser men could admire them — although likely not armored head to toe.

Pirojil was beginning to be annoyed at the lack of reception.

Ellegon or no Ellegon, protocol would have called for somebody — somebody important — to come out and greet such visitors, and Pirojil was willing to wait for that to happen … until Kethol — until Forinel started to stoop to pick up his own rucksack.

Pirojil snatched it away from him.

Idiot.

“Allow me, Your Lordship,” he said, only the look in his eyes adding: You idiot — nobles don’t carry their own bags.

He forced himself not to shake his head in disgust. Leria had been trying to teach Kethol how to be a noble, but beyond getting him to learn how to use an eating prong with a proper flourish, and getting him to stop wiping his nose on his sleeve, she had been less than remarkably successful.

For the time being, his awkwardness could be explained away by Forinel’s long absence from Holtun and Bieme, but in the long run, it could easily get them all hanged.

Leria laid a gentle hand on Forinel’s arm, and he met her smile with an expression that reminded Pirojil of a well-trained dog waiting for permission to eat from its bowl.

“Bide a moment, please, Forinel,” she said. “I’m sure it’s just an oversight that you’ve yet to be greeted properly — do let us wait, and send … someone in to announce your presence.”

“A servant, perhaps?” Erenor asked. “It’s always so very pleasant to have a servant, I’ve found. And, well, since the closest thing we have to that is Pirojil, here, I guess he’ll have to do. You may have the honor of carrying the bags, good Pirojil.”

Erenor smiled as he handed his own rucksack to Pirojil, and then loaded Leria’s on top of th

e pile. Wizards didn’t carry their own gear, either, save for the small black leather bag that contained Erenor’s spell books, and which never seemed to leave his hands.

“I thank you for your help, good Pirojil. We shall meet you inside,” Erenor said.

Pirojil didn’t have to ask how Erenor felt about their roles having been reversed, about how it was Pirojil playing the servant — a captain of march, in theory, but a servant in practice, at least for the moment — instead of Erenor. Erenor visibly enjoyed it. Too much.

Pirojil would have enjoyed beating Erenor’s face into a bloody pulp, but that was not on today’s schedule, apparently.

Pirojil tried to act as though he didn’t much care, which would have been somewhat easier at the moment if he wasn’t trying to balance four bags as he walked.

Cursing silently, unable to see his own feet, Pirojil staggered up the steps, almost falling when he reached the top one.

Old Tarnell was waiting for him just inside the door.

He was overdue for some new clothes: his tunic fit him too loosely over the chest and bulged at the belly enough to threaten popping buttons.

But a shiny new bit of silver braid along his shoulder seam proclaimed him the governor’s aide, and it matched the silver captain’s braid on his collar. That and the two officers’ pistols on his belt were the only changes that Pirojil could see: the deep creases in Tarnell’s lined face hadn’t deepened, nor had the plain wooden pommel of his sword’s wire-wrapped hilt been replaced by something more gaudy.

It was a standard barracks joke that the only thing that moved across the ground faster than a good Nyphien warhorse was a newly made captain on his way to the armorer to buy a proper officer’s saber, but Tarnell had kept his own weapon with his new rank.

Pirojil sympathized with that — if he was Tarnell, he wouldn’t have fucked with something that had served him that well for that long out of anything this side of necessity.

And, in fact, he hadn’t, and he had no intention of doing so. The sword at Pirojil’s own waist was still the one he had carried for years: straight and double-edged, not a curved officer’s saber. Its hilt was wrapped with brass wire, instead of some flashy lizardskin that might slip under a sweaty palm, and the pommel was made of plain brass shaped like a walnut. Expensive as it had been, it was still a line soldier’s weapon, not an officer’s. Not flashy, but effective — the blade had been made of good dwarven wootz, and was kept sharp enough to shave with.

The Road Home

The Road Home The Sword and the Chain

The Sword and the Chain Not Quite Scaramouche

Not Quite Scaramouche Guardians of The Flame: To Home And Ehvenor (The Guardians of the Flame #06-07)

Guardians of The Flame: To Home And Ehvenor (The Guardians of the Flame #06-07) The Silver Stone

The Silver Stone Hero

Hero Not For Glory

Not For Glory The Sleeping Dragon

The Sleeping Dragon The Fire Duke

The Fire Duke Guardians of The Flame: To Home And Ehvenor (Guardians of the Flame #06-07)

Guardians of The Flame: To Home And Ehvenor (Guardians of the Flame #06-07) Hour of the Octopus

Hour of the Octopus Emile and the Dutchman

Emile and the Dutchman The Crimson Sky

The Crimson Sky Guardians of the Flame - Legacy

Guardians of the Flame - Legacy The Silver Crown

The Silver Crown Not Exactly The Three Musketeers

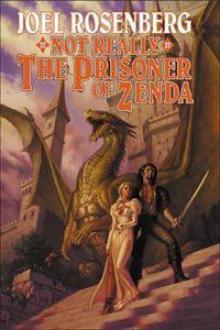

Not Exactly The Three Musketeers Not Really the Prisoner of Zenda

Not Really the Prisoner of Zenda