- Home

- Joel Rosenberg

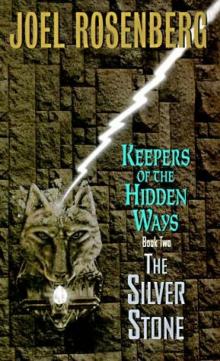

The Silver Stone

The Silver Stone Read online

The Silver Stone

Keepers Of The Hidden Ways

Book II

Joel Rosenberg

Content

Prologue War, and Rumors of War

Part One Hardwood, North Dakota

Chapter One Homecoming

Chapter Two The Best—Laid Plans

Chapter Three Decisions

Chapter Four Another Homecoming

Part Two Tir Na Nog

Chapter Five Avoidance Play

Chapter Six Harbard’s Landing

Chapter Seven Margrave Erik Tyrson

Chapter Eight Minor Betrayals

Chapter Nine “The Best fruit…”

Chapter Ten Sparring Rules

Chapter Eleven Rumors

Chapter Twelve Marta

Chapter Thirteen Harbard’s Landing

Chapter Fourteen To the Seat

Chapter Fifteen Storna’s Stele

Chapter Sixteen The River

Chapter Seventeen The Seat

Chapter Eighteen Introductions

Chapter Nineteen Decisions

Chapter Twenty The Table

Chapter Twenty-One The Mouth of the Wolf

Chapter Twenty-Two A Farewell

Chapter Twenty-Three Harbard’s Crossing

Author’s Note

Prologue

War, and Rumors of War

The dusk is fully ended,

And remnants of twilight have fled.

Horses have been settled in their stables,

And children put to bed.

But before the day ends,

And before the day dies,

The Hour of Long Candles comes,

The Hour of Long Candles arrives,

The Hour of Long Candles appears,

The Hour of Long Candles arrives.

—Traditional Vandestish Chant,

Used To Announce The End Of The Day

Harbard swung the double-bladed axe with a slow, even rhythm, relishing the feel of the smooth handle against his right hand, the shock of the sharp, bright head biting into the wood, the spray of chips and the turpentine smell as he brought the axehead back, spun the axe half around, and then swung again, and again.

He could have called upon a fraction of his old strength and hacked through the trees as easily as he had more than once hacked through a battlefield full of enemies, but he had long since lost his taste for such things.

Amazing, really, for one who had waded through rivers of blood to now eschew even an easy slaughter of a tree.

He had started with the undercut, properly low, facing in the direction he wanted the tree to fall, and men walked around the base of the tree and started in on the other side. The old pine was stronger than he had expected: the final cut almost met the undercut before, with loud cracks of protest, the tree started to lean, and then to fall.

The butt-end of the tree kicked back against his shoulder, sending his axe flying end over end one way, kicking Harbard back easily his own length, knocking him flat.

With a swallowed curse—he had long ago learned to curse only deliberately—he rose, dusting himself off, working his shoulder, trying to pretend it didn’t hurt. Had he been braced for it, he could have resisted, but he had been lazy and sloppy in his old age, and he hadn’t expected it.

Old one, he thought to himself, it’s as well you’ve long ago put yourself out to pasture. Even just a century ago, he wouldn’t have stood in the way of a tree he was chopping.

Oh, well. He picked up the axe and walked to the base of the fallen pine, stripping off wrist-thick branches with quick strokes of the axe, only stopping when the trunk thinned out a few bodylengths from the top. He quickly severed the top of the tree, then set his axe down and stripped off the bark with his fingers, shoving them through the rough bark, peeling the tree like a banana. There was something pleasurable about chopping the tree the way an ephemeral would, but stripping the bark with the axe while avoiding cutting into the wood would be a tedious task, and Harbard drew a careful distinction between regularity and tedium.

In minutes, what had been a tree was a naked log and a scattering of bark and branches that would have to be dealt with later, as when they dried they would become violently flammable tinder.

He found the center of the log and moved back a careful step toward the base to allow for its greater thickness, then stooped to pick it up by its balance, hefting it to his shoulder with a grunt. It was heavy. The trees seemed to get heavier each decade.

His bare feet sank ankle-deep into the packed dirt of the path that led downhill, past his cottage, toward the ferry landing. More than two dozen logs lay in a single row, crosswise across two short lengths of stone fence, aging and drying in the sun; Harbard set this one down on the newer end of the pile, using a series of small wooden wedges to separate it from the next one over, then set his hands on his hips.

Enough? It was hard to say. Maintaining his ferry barge was a matter of constantly replacing rotting logs, and while it was a certainty that the ones that now made up the floor of the barge would need replacement, it was not at all a certainty when.

Harbard allowed himself a grin. That was true for so much else.

High above in the blue, cloud-spattered sky, a raven slowly circled down, riding wind currents with its huge wings, never so much as flapping.

“Greetings, Hugin,” Harbard said, in a language that was older than the sagging hills that rose behind the cottage. “What word have you?”

“War,” the raven cawed. “War, and rumors of war.”

Harbard sighed. There had been a time when such would have excited him, when the thought of the clash of axes and the clatter of spears would have aroused a fervor within him. Brave men facing other brave men, all competing for the honor of being noticed by Harbard and his friends, in life or in death…

But that time was long past, and Harbard preferred things quieter these days.

“Tell me,” he said.

Part One

Hardwood, North Dakota

Chapter One

Homecoming

“You want to try and land it, Ian?” the redheaded pilot shouted over the roar of the Lance’s single engine.

Even after more than two hours in the air, Ian was still surprised by how loud it was.

Ian Silverstein shook his head. “Thanks, but no thanks.” His chuckle was tight in his chest, and his hands clenched the steering yoke. It had probably been a mistake to ask if he could fly it a little. Ian had been joking, but Greg Cotton had said yes, then flicked off the autopilot when Ian put his hands on the steering yoke, well before Ian had put his feet on the rudder pedals.

Ian was surprised to find that flying really wasn’t all that hard, but it was nervous-making. And it was one thing to try to hold the small plane steady and level—he kept having to push the nose down, or the plane would climb—but it would be another thing to try to line it up with the landing strip that was what Karin Thorsen had laughingly referred to as Hardwood International, and yet another thing to try to put the plane down.

Besides, Greg was kidding. At least, he thought Greg was kidding.

“Okay,” Greg said. “I’ve got it.”

“Eh?”

“I said, ‘I’ve got it.’ That means I’m flying now. You can let go. Honest.”

The breath came out of him with a rush, and Ian let himself sag back in the right-hand seat as he wiped the palms of his hands on his pants.

Two thousand feet above Hardwood, North Dakota, the sky was clear and the air was smooth, with no trace of the turbulence that had marked the Lance’s descent through the wispy layer of clouds now more than a mile overhead.

Greg put the plane into what he claimed was a shallow, on

e-minute turn, and while the turn indicator seemed to say he was telling the truth, Ian’s stomach was sure he was lying through his teeth. It felt like he was laying the plane over on its side.

Still, through the bug-spattered windshield, it gave Ian a good view of Hardwood. What there was of it. A granary and a dozen or so stores lining Main Street on the western side of town; the municipal swimming pool—which probably got used all of two, maybe three, weeks of the year, given the weather—and the football field and school on the other, and between them perhaps a few hundred houses on the elm-lined streets.

“What’s the population?” Greg asked. “About fifty?”

Ian chuckled. “Not quite that small. A couple of thousand.” That was, maybe, a little misleading. Hardwood served the surrounding farms and tinier towns, as well, enough people that it had its own, albeit small, high school. The new clinic next to Doc Sherve’s house had the only emergency room between Thompson and Grand Forks, staffed by overpaid doctors from a commercial service on weekends and during Doc’s increasingly frequent vacations.

But the airport, such as it was, was little more than a pair of hangars, and an asphalt landing strip about a thousand yards long, broken in spots where weeds had pushed through.

It looked a lot shorter from the air than it had from the ground.

“How long is that?” Ian asked.

Greg glanced down at the Jeppson chart in his lap. “Twenty-three hundred feet. No problem.”

“You can put it down there?” It looked awfully short.

“Down?” Greg sniffed. “Down is not a problem. I could look up in the manual what the specs are for landing this thing if you don’t have to clear a fifty-foot obstacle, but it’s not going to be more than a thousand feet. Landing’s not a problem. Now, taking off’s a different story… Might be a bit tight taking off on a hot day with a full load, no wind, and a full tank, but hey, it’s cool out, it’ll be just me in here, there’s only about forty, forty-five gallons in the tanks, and I’ve got about five, ten knots of headwind. Easy.”

He offered Ian an Altoid—Ian declined with a quick headshake; they were too strong for his tastes—then popped a couple of the pill-like mints in his own mouth before closing the tin and dropping it to his lap.

“Two kinds of pilots,” Greg said, as he reached forward and flipped the switch for the landing gear, nervously tapping against the three green lights until they came on. “The kind that’s made a gear-up landing, and…”

“The kind that hasn’t?”

“Nah. The kind that will,” he said, easing back on the throttle and reflexively pointing toward first one dial, then another. “Which is why they charge more for the insurance on these retractable-gear jobs. Okay; looks good.” He pushed the nose down, then up as he eased back on the throttle. “And we’re… down.” The plane bounced once, then settled down to a bumpy roll across the asphalt.

Greg let it almost come to a stop, then turned it around and eased it off the runway before cutting the power.

After the racket of the engine, the silence in the small cabin was deafening.

“Looks like we made it,” Greg said with a grin.

Ian was already out of his seatbelt and opening the door. It was lighter than it should have been. That was the funny thing about these small planes—the metal skin was only about the thickness of an old-style beer can. It seemed too light, too flimsy to serve its purpose.

Then again, Ian thought, maybe that’s true for me, too. He grinned.

He crawled out onto the wing and lowered himself to the tarmac. Greg followed, dropping to the ground with a practiced step-and-bounce off the mounting Peg. Ian took a deep breath as he walked around to the other side and the door to the passenger compartment, letting Greg open it. It didn’t feel solid, like a car door; Ian was half afraid he was going to tear the door off if he handled it.

Greg reached in and handed out Ian’s blocky black leather travel bags, a matched set, designed to fit underneath a commercial airplane seat or in an overhead luggage rack, and the cheap canvas golf bag Ian used for his fencing gear.

And for Giantkiller. Which you could call fencing gear, if you wanted to.

“You want me to watch the stuff while you walk into town and see about borrowing a car?” Greg asked. “You’ve got a fair walk if nobody shows up to meet you.”

Ian shook his head. “Nah. I’ll just stash the bags over in the shade of the hangar and walk into town.” Amazing how quickly he was taking to small-town ways. Six months ago, he would no more have considered leaving his bags than he would have considered leaving his wallet. “There’s no need to wait—unless you’re going to change your mind and stay for dinner. Karin Thorsen’s fried chicken and biscuits are pretty special.” Ian’s mouth watered at the thought of biting through that crunchy skin and into the moist meat beneath. Maybe it was that the chickens were grain-fed, and from the Hansen farm, or maybe it was the seasonings Karin used, or maybe it was just magic.

Bullshit. Her cooking was good, but the chicken could have been overcooked to tasteless rubberiness, and he still would be looking forward to dinner.

What it was, was that he was coming home.

“Wish I could, but I’ve got to get the plane back.” Greg sealed the rear door closed, then gave it a friendly pat. “Next time, okay?”

“Fair enough.” Ian reached for his wallet. “How much do I owe you for the gas?”

“Well…” Greg frowned. “We used about thirty-two, thirty-three gallons flying up. Figuring that the wind holds, it’ll be about a hour and a half—maybe twenty-five gallons—back. I can use my company card and get it for about two bucks a gallon.”

“Good deal. And thanks. You might as well top the tank off for Jake as long as you’re filling up.” Ian pulled eight twenties out of his wallet and handed them over. “Thank him for me, and I owe you dinner, next time I’m back.”

“Sounds like a plan.” Greg tucked the bills in his jeans and climbed back up into the plane, locking the door behind him.

“Take care,” he said through the window. He belted himself in and shouted “Clear!” before closing the pilot’s draft window and starting the engines.

Ian already had his bags in the shade of the main hangar; he dropped them and waved.

The little plane rolled toward the far end of the runway, slowly turned around, then accelerated down the runway and lifted off into the air before it was even two-thirds of the way along it, climbing leisurely into the blue sky before it banked away, heading back southeast, toward Minneapolis.

And then it was quiet.

The wind whispered through the grasses, and far off in the west, past the windbreak of trees that must have been a half mile away itself, some distant farm machine was growling, but Ian couldn’t have told what it was even if he was closer. What there wasn’t was somebody noticing a landing at the airport and driving out to investigate.

No problem, though. Ian was back earlier than he had been expected. That was the plan, actually. There was no point in complaining when things turned out the way you wanted. Karin had asked if it was convenient for him to come home earlier than he had planned, and while she wouldn’t talk about why on the phone, that was fine with Ian. Lying on the beach was getting boring anyways, and while he had been surprised to find a fencing club in Basseterre, none of the locals was much competition, except for one saber player who was particularly good at those silly flicking touches that were fine for scoring points, but nothing more.

Ian had to chuckle. It wasn’t too long ago that he thought the purpose of a sword was to score points.

It was time to come home, and if that meant asking a friend to borrow a plane so he could arrive sooner, that was fine, and if it meant walking a couple of miles, that was no big deal, either. He had walked further than that in his time, and likely would again, although not soon.

Spring, maybe. Spend the winter studying swordsmanship with Thorian del Thorian the Elder, bowmanship with Hosea, and hand-

to-hand with the deceptively fast Ivar del Hival, and come spring he’d be ready.

Preparing for it all was, well, it was fun. Getting ready is half the fun, Benjamin Silverstein used to say. Ian’s father was an abusive asshole, but even a stopped clock was right twice a day.

He reached into his golf bag and pulled out the package that contained an epée, a foil, a saber, and Giantkiller’s scabbard. It was a canvas sheet, tied at both ends with a length of soft cotton rope that also served as a sling. He slung it over his shoulder like a quiver. One thing to leave most of what he owned in this world out at the landing field, but another thing entirely to leave his sword there.

He started walking along the left side of the road, long arms and legs swinging to eat up distance quickly.

Hardwood International Airport—so read the hand-painted sign at the turnoff onto the dirt road; it wasn’t just Karin’s joke—was just over a mile outside of town, but the Thorsen house and Ian’s own room at Arnie Selmo’s were over on the far side of town, maybe half an hour away by foot.

The county road was slightly convex, with a broad shoulder leading to a steep drop-off down to the black soil of the fields below. It was hard to tell what had been growing here—at least it was hard for Ian, who was still basically a city boy. Not corn—there still would be cornstalks. Maybe potatoes?

A red-winged blackbird sitting on a post of the wire fence at the edge of the field eyed Ian skeptically as he walked by.

Somebody walking down the road wasn’t a common sight hereabouts, he supposed.

“Well,” he said, “I haven’t seen a lot of red-winged blackbirds, either.”

The bird didn’t answer. He didn’t really expect it to.

A car whizzed by, pulling along dust and sand in its wake; Ian turned his head away and closed his eyes to protect them from the grit. It was doing at least seventy, fairly typical for this part of the world, what with roads straight as an arrow, running sometimes tens of miles without so much as a tiny bend.

It was out of sight before he heard another car approaching from the rear, and again turned away, but instead of it rushing by, he heard this one slow and pull over to the shoulder, sand crunching beneath its tires as it ground to a stop.

The Road Home

The Road Home The Sword and the Chain

The Sword and the Chain Not Quite Scaramouche

Not Quite Scaramouche Guardians of The Flame: To Home And Ehvenor (The Guardians of the Flame #06-07)

Guardians of The Flame: To Home And Ehvenor (The Guardians of the Flame #06-07) The Silver Stone

The Silver Stone Hero

Hero Not For Glory

Not For Glory The Sleeping Dragon

The Sleeping Dragon The Fire Duke

The Fire Duke Guardians of The Flame: To Home And Ehvenor (Guardians of the Flame #06-07)

Guardians of The Flame: To Home And Ehvenor (Guardians of the Flame #06-07) Hour of the Octopus

Hour of the Octopus Emile and the Dutchman

Emile and the Dutchman The Crimson Sky

The Crimson Sky Guardians of the Flame - Legacy

Guardians of the Flame - Legacy The Silver Crown

The Silver Crown Not Exactly The Three Musketeers

Not Exactly The Three Musketeers Not Really the Prisoner of Zenda

Not Really the Prisoner of Zenda